By Amar Jaleel

Translated from Urdu by

Maqbool Ahmed Siraj

The story goes back to days prior to Partition. I and Asha were students at the Ratan Talao Primary School on Temple Road. The school was ranked among the best primary schools of Karachi. It still stands there very much, but is clearly past its prime. It has a desolate look about itself. I don’t know why the name of Temple Road was changed but it remains Temple Road in my memory. Even the M. A. Jinnah Road is same old Bunder Road for me. On one side Temple Road ends at Urdu Bazaar while on the other end it bends at Regal Chowk and proceeds towards Sadar.

My and Asha’s ancestors had shared neighborhoods for well over a century. Love bound the two parivars (families) intimately into spiritual ties which also took inspiration from Saint Sachal Sarmast. The ties were drenched deep in sufistic colours.

I and Asha studied at Ratan Talao School from 1942 to 1946. The school would begin with morning assembly at 10 am and all of us together sang Rabindranath Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana”¦ and Sir Mohammad Iqbal’s Saare Jahan se Achcha”¦ loudly. At the strike of the twelfth hour, the children would gather beneath the trees to share their lunch. I now appreciate our parents who would never pack such stuff into our lunch boxes that would make the kids from the other community cringe and move away from friends. This was how the Karachiites behaved. Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Parsis, Jews, Bahais, Jains and Buddhists lived amidst complete harmony, respecting each other and avoiding anything that would hurt the others. They headed for their temples, mosques, gurdwaras on the eve of their festivals and others would stand outside to greet the devotees emerging out of those hallowed portals. We were met with warmth and respect in each other’s homes.

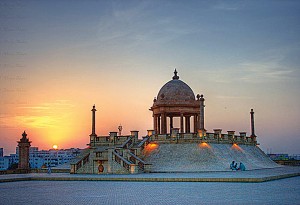

The city of Karachi originated from Kemadi and ended on Tekri, a small hillocks which now hosts the mausoleum of Mohammad Ali Jinnah. A series of kothis (mansions) of Parsee philanthropists stood in a row on the right side of Tekri. Parsee philanthropy has left indelible imprint on Karachi’s cityscape. The stone canopy at the famed, fashionable Clifton and the broad, red sandstone staircase that descends down to the Arabian Sea further ahead, were built by Jehangir Kothari. But the sea has drifted miles away from Jehangir Kothari Parade today. The sea waves used to lash against the historic mound at the Parade where stood the Sai Peer Abdullah Shah Ghazi’s mausoleum. Sweet water used to gush out in a stream from the foothills of the mound. I have not visited it since decades and know little about the transformed topography of modern Karachi. Karachi had just about three lakh souls then. But today it bustles with humanity.

I and Asha spent our recess hour at the Ratan Talao School for four years. Asha would play cricket with me instead of her own gender mates. Besides Asha, there were two more Ashas in my class, one Asha Gidwani and another Asha Lal Chandani. Teachers would teach history to us without any fear of the British administration. They would tell us that this country is our motherland and we need to liberate our mother from the clutches of the British.

We finished our primary school at Ratan Talao in 1947 and were both enrolled at N. J. V. High School. But by then Karachi had turned somber. Shouts for independence were stilled and replaced by raucous cries for Partition of the motherland. Dread set in. People who had vowed to sacrifice everything to free the motherland, had begun reaching for each others’ jugular. Atmosphere was morbidly depressing. Friendships lay asunder. Distances grew between families who had never known the otherness of the other.

Asha migrated to Mumbai where my mother had spent her childhood. Years later I had penned a short story wherein I had written: “Our land is our mother, and mother cannot be divided. But children split from each other. But look at the irony of the situation, those who divide the motherland, also come to rule over it. Then they use all the tricks in their bag to see that those who were separated, should not come together.”

I want to go to India with bouquets of flowers of affection in my hand. I want to look for Asha. I don’t know where she would be, in Kashi, or Brindavan or Haridwar. But I sob whenever I am alone. I sob for the separation that the division of this motherland has caused between us. I was born in 1936 and I am approaching 80th spring of my life. I was born a Hindustani and deep down, some parts of me still whisper, “You are a Hindustani even now”. It is a historical reality.

(This is English rendering of column titled ‘Aman ko Asha se milne do’ appearing in Urdu daily Jung, Karachi in its edition dated October 22, 2013).

COMMENTS