The title of the book “Madrasa Education in Jammu & Kashmir” gives the impression that the book is only about the madrasas of J&K. Of course, there is a Directory of madrasas in J&K, but the book extensively traces the history of madrasas in India and counters much of the criticism allegedly levelled against the madrasas.

AAEENA-E-MADARIS

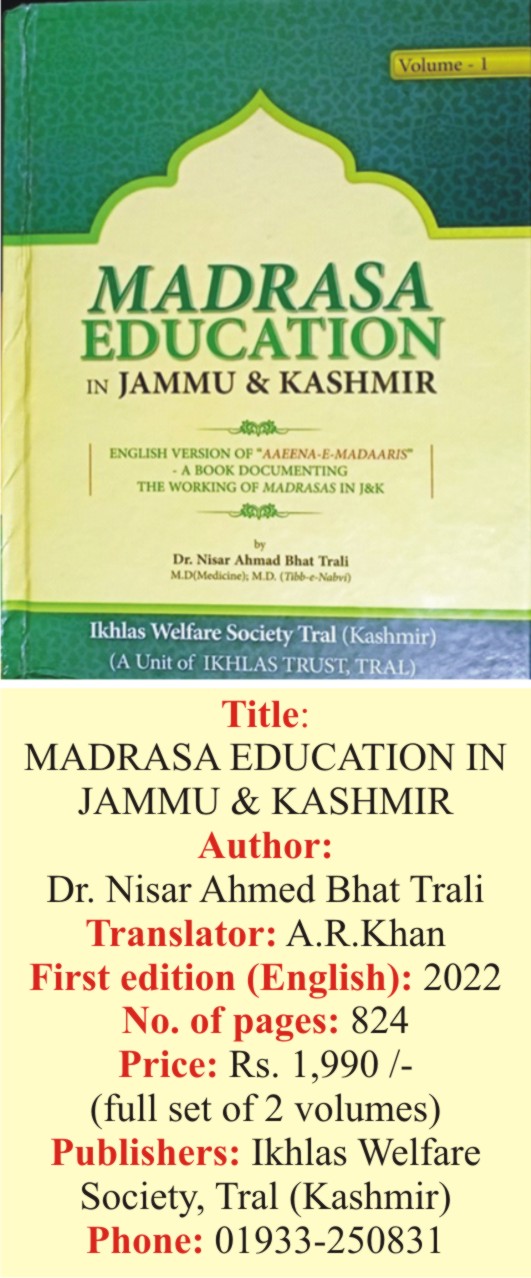

This book is the English translation of the book “Aaeena-e-madaris” (2015) written in Urdu by Dr. Nisar Ahmed Bhat Trali who is a doctor by profession having done his MD (Medicine) and MD (Tibbe-e-Nabvi). The strenuous efforts put in by the author to write this book can be gauged from the fact that “Aaeena-e-madaaris” comprises 1520 pages in two big volumes. The author travelled about 22,000 km in challenging terrain and spent about sixty nights in different madrasas to collect the data. Out of the 499 existing madrasas, the author says 49 madrasas did not cooperate. The book has information about 450 madaris (plural of madrasa), of which 186 are located in Jammu province and 264 in Kashmir province.

THE ORIGIN OF MADRASAS

Adjacent to Masjid-e-Nabvi in Madinah, a shaded platform called Sufffah existed during Prophet Muhammad’s (peace be upon him) time to impart education and this was the first madrasa in Islamic history. The author elaborates that there were arrangements for “Night Schooling” at Suffah so that people engaged during day time could also receive the benefit of education. Prophet Muhammad (SAW) established special educational institutions for Bedouin tribal Muslims in different Arab tribal regions.

Thereafter, the author traces the history of madrasas in the Islamic world. Mahmud of Ghazni, founder of the Ghaznavid dynasty who ruled from 998 to 1030 gets the credit for shaping the madaris in the present form. The Jamia Masjid in the capital city of Ghazni also had a madrasa with a library attached to it.

MADRASAS IN INDIA

Moving over to India, the author states that during Sultan Mohammad Tughlaq’s rule (1325-1351) there were 1000 madaris in Delhi where apart from religious education, logic and mathematics were also taught. His successor Feroz Shah Tuglaq (1351-1388) made arrangements for imparting training in skill development to the slaves, in addition to religious education. He established separate madaris for ladies. The famous traveller Ibn Batuta mentioning the place Hanooz in south India records that “the women of this place are Hafiz-e-Qur’an.”

Dr. Nisar Ahmed states that during King Humayun and Akbar’s rule, there was the extra-ordinary expansion of madaris. Aurangzeb established madrasas not only in big cities but also in towns and rural areas. Aurangzeb gifted a grand house, famously known as Farangi Mahal to the Darul Uloom Madrasa Nizamia in Lucknow. For about three centuries, the madaris in India have followed the study curriculum of this madrasa which is popularly called Dars-e-Nizami.

FAMOUS PERSONS FROM MADRASAS

Interestingly the author mentions many prominent poets and writers who received education in madrasas. Faiz Ahmed Faiz became a Hafiz-e-Qur’an from a madrasa in Sialkot. Asrar ul Hassan Khan, better known as Majrooh Sultanpuri, received his education from Madrasa Kanzul Uloom, Faizabad. Kaifi Azmi received their education from the famous Sultan-al- Madaris of Lucknow. Altaf Hussain Halee was a product of Madrasa Hussain Baksh, Delhi. Allama Shiblee Nomanee, Allama Neyaz Fatehpuri, Allama Aamir Usmani, Faza ibn Faiz, Rashid Khan and Allama Shafeeq Jonepori were all products of madrasas.

The enrolment of Hindu students in madrasas was a tradition which existed till the last era says the author. Raja Ram Mohan Roy, the famous Indian reformer and one of the founders of the Brahmo Samaj studied Persian and Arabic in a madrasa. Ustad Ahmad Lahori, the Chief Architect during the reign of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan and who was the key person in the construction of the Taj Mahal in Agra and the Red Fort in Delhi was also a madrasa student according to the author. Curiously, the author calls Ustad Ahmad Lahori a mason! Many of us may not be aware that India’s first President Dr. Rajendra Prasad received his childhood education from a madrasa in Bihar.

MADRASAS IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR

The book traces the history of madrasas in J&K from the 14th century. Kashmir from 1339 CE to 1586 CE was under the rule of Shahmiri and Chak Sultans. During this period Kashmir made unparalleled progress in art, knowledge, literature and history. Much before Akbar had established the Darul Tarjuma (Department of Translation), Kashmir was already working on translations. Sultan Zainulabdeen deputed his men to Turkey, Iraq and many places in India to procure Persian, Arabic and Sanskrit documents. Sultan Zainulabdeen, Sultan Qutubudeen, Sultan Haider Shah and Sultan Yousuf Shah Chak not only promoted madrasas with religious and temporal education but were themselves, first-rate poets. The first poetess of this era was Lala Arifa. During the rule of the Sultans and particularly during Zainulabdeen’s time, history, medicine, botany, chemistry, and many other subjects were taught in madrasas. Students were also being trained in archery, swordsmanship and horse riding. The Sultans endowed jagirs to the madrasas and therefore every village had a madrasa. Kashmir under the rule of the Sultans had been the hub of knowledge and literature.

DIRECTORY OF MADRASAS

I dwelled more on the introductory chapters of the book since they give rare insights into the history of madrasas. But the main thrust of the book is to enlist the madrasas in J&K in the form of a Directory. Each of the 450 madrasas listed has information about their location, background, students’ enrolment, curriculum, administrative pattern, infrastructure, financial details, the number of pass-outs, hafiz-e-Qur’an, visiting dignitaries and many other details. The pains taken by the author to collect such voluminous details are really astonishing. Of the 450 madaris, 340 are associated with Islamia Arabia Darul Uloom Deoband and the remaining belong to other schools of thought. Totally, the number of students enrolled in these madrasas as boarders is 24,665 and they have 4646 teachers and 1126 other employees. 2500 scholars have qualified from these institutions besides 19,000 Hafiz. 210 publications have been brought out. The books available in the library of these madaris is 3,90,000. Modern schools are established in 94 madrasas and computer facilities are provided in 108 institutions says the author. However, the mere availability of computers is not a yardstick, but whether computer training is being given is a moot question. It would have been commendable if the author had estimated the number of children getting formal education from recognized schools. The book also deals at length with the biographies of the founders. Interspersed are quotations of eminent persons and Ahadees.

CONCLUSION

There is a chapter captioned “A passionate appeal to the nation…..” which in reality is an address to the students of the madrasas. It paints a stereotyped picture of poor, sacrificing madrasa students pitted against rich and cruel men. This is a trite and superfluous chapter which could have been omitted. The translation and printing of the book is quite good. However, the editing of the book could have been better. Some articles are published before the Directory and some after the Directory section. All the articles could have been in one place, preferably before the Directory. The book is both a treatise on madrasas and also a Directory of madrasas in J&K. Despite the fact that the madrasas nowadays take the flak, sometimes unfairly, they have been rendering yeoman service for generations in providing basic and intensive religious education. This book holds a brief for madrasas in order to recognize their invaluable services. It does not dwell on their need for reformation and modernization which is an inadequacy. The strenuously compiled information about the 450 madrasas is a herculean effort and will prove to be useful as a Data Bank. Every library should have a copy of this book.

COMMENTS