Such is the emphasis on perfection today that even a difference of a 50th of the human hair’s thickness could cause modern-day gizmos to malfunction and rockets to go haywire.

Exactly, How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World

By Simon Winchester

William Collins

2017, 370 pages, Rs. 599.

By Maqbool Ahmed Siraj

Precision is a vital necessity of the modern-day life. Imagine the terrible consequences of a car cruising at a speed of 100 miles an hour on misaligned wheels, or a sewing machine failing to deliver stitches at regular intervals, or a faulty oxygen pipe of an operation theatre! Historically it has been tellingly summed up in the proverb, ‘For want of a nail, a kingdom was lost’. What this implies is that seemingly minor omissions could lead to grave tragedies.

Precision is an integral, unchallenged and seemingly essential component of our modern landscape. It pervades our lives entirely comprehensively. Author Simon Winchester spins a tale around man’s quest for perfection, exactitude and precision, which led him on the trajectory of Industrial Revolution, beginning from James Watt’s steam engine and ‘Ironmaster’ John Wilkinson’s technique for manufacturing guns in 1774. Officially, Wilkinson is described to be the father of precision.

Fathering Precision

Wilkinson began to do business with James Watt by 1775. He merged the steam power with cannons. When water is heated to boiling point, it turns into gas and occupies 1,700 times more volume than the water and attains great propulsive power. Watt’s steam engine and Wilkinson’s cannons added great firepower to the British Navy. James Watt put it like this: Mr. Wilkinson has bored us several cylinders almost without error, that of 50 inch diametre”¦does not err the thickness of an old shilling at any part. Old English shilling had a thickness of a tenth of an inch. Precisely, it was the moment precision took birth. The cannons supplied to the British Navy enabled the Kingdom to turn most wars to its advantage and expand its sway to unseen boundaries.

Joseph Bramah, known to be the designer of unbreakable locks, took precision to the next stage. Bramah’s lock got patented and remained unbreakable for long time to come.

Standardization

Honore Blanc brought standardization in gun-making of France, ensuring that all the component parts of a flintlock be made as exact and faithful copies of the one perfectly- made master. This entailed coming up with gauges and moulds. A demo put up before Thomas Jefferson, then American envoy to France in 1785 (later to become the President of America), took the idea of standardization beyond the Atlantic. The gun industry flourished in Connecticut Valley, which came to be known as Gun Valley. Precision started to become an international phenomenon. Isaac Singer introduced precision into the manufacturing of sewing machines. Cyrus McCormick was creating reapers, mowers and later combined harvesters. Albert Pope came up with bicycles for the masses.

Change was all-pervasive in Europe. Railways were snaking into every nook and corner of Europe, mines were being sunk, chimneys began to belch smoke into the yet unpolluted air and trade unions began to be formed.

Joseph Whitworth (1822-1887), a new devotee of precision, devised screws, self-acting lathes, planning, slotting, punching, drilling and boring machines and came up with the British Standard Whitworth (BSW), which created an accepted standard for screw threads.

Gathering Wheels

By the turn of the new century, the time was ripe for precision to enter the automobile industry. Henry Royce set up a workshop in Manchester to create ‘the finest car’ for the discerning few, and Henry Ford laid a plant in Detroit to mass produce cars that everyone could afford. London aristocrat Charles Rolls who was mesmerized after seeing the photograph of the fine creation, teamed up with Henry Royce to set up the Rolls-Royce unit. The car”for critics, the vulgar face of capitalism”known for accuracy and mechanical perfection, was machined down to the finest and most unforgiving of tolerances. It represented the motoring acme, its examplar.

The first Ford Model A car rolled out in 1908. The Ford car, according to Henry Ford, ‘was made of a few parts and every part does something’. If Rolls-Royce epitomized perfection, Ford stood for production. The Ford T Model sold 16,500,000 units in 19 years. A Ford car was rolling out of the assembly line every 40 seconds.

Over the High Seas

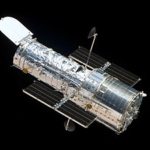

An oil rig borer would call himself precise if he was able to land the rig on the ocean floor within 200 feet of the place marked X on a chart. But by today’s standards he will be called imprecise, a total failure. Places on the surface of the planet can now be located within centimetres, even millimetres, thanks to the Global Positioning System (GPS), which many of us happily use in cell-phones and cars.

GPS for the New World Order

GPS was born out of the need of the new world order, which demanded something better, quicker, more reliable and much more secure. It owes itself to the US Air Force’s Navstar Global Positioning System, which they started building in 1973. Though it was exclusively for military use, it was allowed for civilian use. There have been 70 GPS satellites put into medium Earth Orbit, about 12,000 miles, 31 remain. They were all manufactured by US weapon manufacturer Lockheed Martin. It is this system that enabled the US to precisely target the Libyan dictator Qaddafi in his Presidential palace or the militant Anwar Awalaki in his hideout in Yemen. All 31 satellites are checked by a Master Control Station and a network of 16 monitoring stations around the world. Now, there is also a pan-European system called Galileo. A Chinese system, Beidou, is up and running and will presumably soon become as ubiquitous as GPS.

Into the Computing Age

The invention of transistors and chips started the era of ultra-precision. In 2014, the four major chip-making firms were making 14 trillion transistors every single second. In 1947 a transistor used to be of the size of a child’s hand. In 1971, the transistor in a microprocessor were just ten microns wide, a tenth of a diameter of a human hair.

Time Machines

The quartz revolution in Japan in 1969 brought down the Swiss watch industry to its knees. There were 1,600 Swiss watch houses. By the end of the next decade, there were only 600, and the workforce had been cut down to a quarter of its former level. Japanese watches not only ended the daily or weekly winding, but almost eliminated the timing adjustments as most previous watches would run faster or slow down over a certain period. In fact, the Japanese word ‘Seiko’ stood for ‘exquisite workmanship’ or ‘precision’. Interestingly, most of these precision-studded tools, gadgets and equipment came from five countries: the United Kingdom, United States, France, Germany and Japan, with a smattering from Italy, Switzerland and the Netherlands. n

COMMENTS