In Morocco, the oldest Arab Kingdom, coexistence was recently given a glimmer of hope with the opening of the BaytDakira, a spiritual and heritage space that seeks to preserve and enhance the Judeo-Moroccan memory in the old city of Essaouira. The museum is the latest in a long line of efforts to restore and redefine North Africa’s Jewish roots.

Morocco’s King Mohammed VI has visited the country’s newly-opened ‘House of Memory’, showcasing historic Jewish-Muslim relations and coexistence in the coastal city of Essaouira. The Jewish community in Essaouira was once so numerous that there were 37 synagogues, with many families having arrived after their mass expulsion from Spain by the Catholic king in 1492. The new museum is housed in one such synagogue, built with carved woodwork by a wealthy merchant, adjoining his house, and details the life of Moroccan Jews. It includes the families and descendants such as Lord Belisha, Britain’s minister of transport, finance and war during the 1930s and 40s, whose appointment to the post of minister of information was blocked for antisemitic reasons. His name is now known for the amber ‘Belisha beacons’ at pedestrian crossings. BaytDakira “testifies to a period when Islam and Judaism had closeness,” said the king’s adviser.

The tale of Al-Yahud Al-Maghariba (the Moroccan Jews) is not one that is often told. At their peak in the 1940s, they made up about 5 percent of the country’s population and were critical to Morocco’s trading businesses and guilds of craftsmen. After the creation of the state of Israel, the community dispersed, some owing to panic and others to “Operation Yachin,” a policy to encourage the migration of Jews from Morocco to Israel. But, as the stories of Libyan, Iraqi, Yemeni and Syrian Jews have been lost amid the conflicts of the Middle East, the Jews of Morocco are not just surviving, but thriving in a country they have called home for thousands of years.

To the Moroccan authorities, the country’s Jewish community is a living symbol of its persistence as a religious sanctuary. For many centuries, the country’s sovereigns have issued “dahir” decrees, according protection to communities and freedom of worship. In every Moroccan city, the “mellah” (Jewish quarter) is almost an annex of the sultan’s palace, reflective of the symbiotic relationship between the country’s primary executive and religious power and its Jewish business community. It was, therefore, only fitting that King Mohammed himself opened the BaytDakira, echoing the policy of his grandfather and namesake, who rejected Nazi orders to deport the country’s Jewish community. “There are no Jews in Morocco; there are only Moroccan citizens,” was his response to the Vichy government of France’s request to turn over Jews. He added: “I reiterate as I did in the past that the Jews are under my protection, and I reject any distinction that should be made among my people.” While other rulers made common cause with the Nazis, Mohammed V, as “Commander of the Faithful”, exercised his authority in the protection of not only Muslims, but all of his Jewish and Christian subjects too. During the course of the Second World War, not a single Moroccan Jew was handed over to the Nazi authorities.

The BaytDakira is part of a wider effort to restore the country’s Jewish legacy. This has included the renovation of a dozen synagogues, 167 Jewish cemeteries and 12,600 graves in recognition of the importance of Morocco’s Jewish heritage. In an era when issues in the ‘Holy Land’ have massively skewed the narrative of the Jewish role and contribution to Muslim societies, the case of Morocco is incredibly important. Some of the most prominent political, academic and cultural figures to originate from the Arab world in the last few centuries have been Maghrebi Jews.

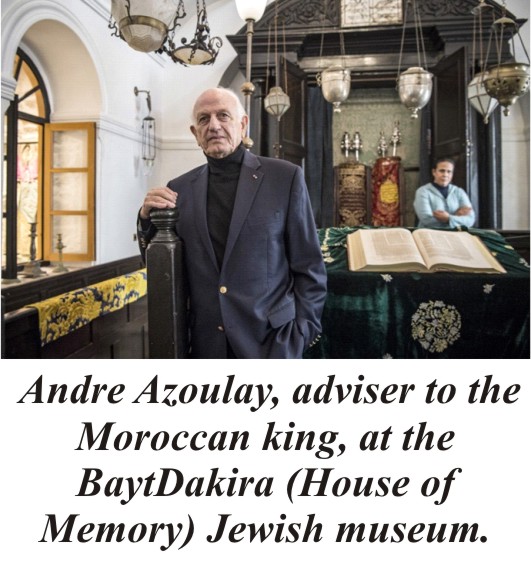

To Andre Azoulay the current king’s trusted adviser, who is touted as the most powerful Jew in the Muslim world projects such as BaytDakira are as much about correcting stereotypes and misconceptions as they are about preserving heritage. Speaking at the opening, he stated that in rejecting “amnesia, regression and archaism,” what was once the region’s only Jewish-majority city can now stand as an example of the diversity and cultural richness of living together.

COMMENTS